THE ART OF LISTENING

Article by Eldin Hasa

Eight barriers to effective listening

More attention is usually paid to making people better speakers or writers (the "supply side" of the communication chain) rather than on making them better listeners or readers (the "demand side"). The most direct way to improve communication is by learning to listen more effectively.

Nearly every aspect of human life could be improved by better listening -- from family matters to corporate business affairs to international relations.

Most of us are terrible listeners. We're such poor listeners, in fact, that we don't know

how much we're missing.

The following are eight common barriers to good listening, with suggestions for overcoming each.

#1 - Knowing the answer

"Knowing the answer" means that you think you already know what the speaker wants to say, before she actually finishes saying it. You might then impatiently cut her off or try to complete the sentence for her.

Even more disruptive is interrupting her by saying that you disagree with her, but without letting her finish saying what it is that you think you disagree with. That's a common problem when a discussion gets heated, and which causes the discussion to degrade quickly.

By interrupting the speaker before letting her finish, you're essentially saying that you don't value what she's saying. Showing respect to the speaker is a crucial element of good listening.

The "knowing the answer" barrier also causes the listener to pre-judge what the speaker is saying -- a kind of closed-mindedness.

A good listener tries to keep an open, receptive mind. He looks for opportunities to stretch his mind when listening, and to acquire new ideas or insights, rather than reinforcing existing points of view.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

A simple strategy for overcoming the "knowing the answer" barrier is to wait for three seconds after the speaker finishes before beginning your reply.

Three seconds can seem like a very long time during a heated discussion, and following this rule also means that you might have to listen for a long time before the other person finally stops speaking. That's usually a good thing, because it gives the speaker a chance to fully vent his or her feelings.

Another strategy is to schedule a structured session during which only one person speaks while the other listens. You then switch roles in the next session.

"It's worth emphasizing that the goal of good listening is simply to listen -- nothing more and nothing less."

During the session when you play the role of listener, you are only allowed to ask supportive questions or seek clarification of the speaker's points. You may not make any points of your own during this session. That can be tricky, because some people's "questions" tend to be more like statements.

Keeping the mind open during conversation requires discipline and practice. One strategy is to make a commitment to learn at least one unexpected, worthwhile thing during every conversation. The decision to look for something new and interesting helps make your mind more open and receptive while listening.

Using this strategy, most people will probably discover at least one gem -- and often more than one -- no matter whom the conversation is with.

#2 - Trying to be helpful

Another significant barrier to good listening is "trying to be helpful". Although trying to be helpful may seem beneficial, it interferes with listening because the listener is thinking about how to solve what he perceives to be the speaker's problem. Consequently, he misses what the speaker is actually saying.An old Zen proverb says, "When walking, walk. When eating, eat." In other words, give your whole attention to whatever you're doing. It's worth emphasizing that the goal of good listening is simply to listen -- nothing more and nothing less. Interrupting the speaker in order to offer advice disrupts the flow of conversation, and impairs the listener's ability to understand the speaker's experience.Many people have a "messiah complex" and try to fix or rescue other people as a way of feeling fulfilled. Such people usually get a kick out of being problem-solvers, perhaps because it gives them a sense of importance. However, that behavior can be a huge hurdle to good listening.Trying to be helpful while listening also implies that you've made certain judgments about the speaker. That can raise emotional barriers to communication, as judgments can mean that the listener doesn't have complete understanding or respect for the speaker.In a sense, giving a person your undivided attention while listening is the purest act of love you can offer. Because human beings are such social animals, simply knowing that another person has listened and understood is empowering. Often that's all a person needs in order to solve the problems on his or her own.If you as a listener step in and heroically offer your solution, you're implying that you're more capable of seeing the solution than the speaker is.If the speaker is describing a difficult or long-term problem, and you offer a facile, off-the-cuff solution, you're probably forgetting that he or she may have already considered your instant solution long before.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

Schedule a separate session for giving advice. Many people forget that it's rude to offer advice when the speaker isn't asking for it. Even if the advice is good.

In any case, a person can give better advice if they first listened carefully and understood the speaker's complete situation before trying to offer advice.

If you believe you have valuable advice that the speaker isn't likely to know, then first politely ask if you may offer what you see as a possible solution. Wait for the speaker to clearly invite you to go ahead before you offer your advice.

#3 - Treating discussion as competition

Some people feel that agreeing with the speaker during a heated discussion is a sign of weakness. They feel compelled to challenge every point the speaker makes, even if they inwardly agree. Discussion then becomes a contest, with a score being kept for who wins the most points by arguing.

Treating discussion as competition is one of the most serious barriers to good listening. It greatly inhibits the listener from stretching and seeing a different point of view. It can also be frustrating for the speaker.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

Although competitive debate serves many useful purposes, and can be great fun, debating should be scheduled for a separate session of its own, where it won't interfere with good listening.

Except in a very rare case where you truly disagree with absolutely everything the speaker is saying, you should avoid dismissing her statements completely. Instead, affirm the points of agreement.

Try to voice active agreement whenever you do agree, and be very specific about what you disagree with.

A good overall listening principle is to be generous with the speaker. Offer affirmative feedback as often as you feel comfortable doing so. Generosity also entails clearly voicing exactly where you disagree, as well as where you agree.

#4 - Trying to influence or impress

Because good listening depends on listening just for the sake of listening, any ulterior motive will diminish the effectiveness of the listener. Examples of ulterior motives are trying to impress or to influence the speaker.

A person who has an agenda other than simply to understand what the speaker is thinking and feeling will not be able to pay complete attention while listening.

Psychologists have pointed out that people can understand language about two or three times faster than they can speak. That implies that a listener has a lot of extra mental "bandwidth" for thinking about other things while listening. A good listener knows how to use that spare capacity to think about what the speaker is talking about.

A listener with an ulterior motive, such as to influence or impress the speaker, will probably use the spare capacity to think about his "next move" in the conversation -- his rebuttal or what he will say next when the speaker is finished -- instead of focusing on understanding the speaker.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

"Trying to influence or impress" is a difficult barrier to overcome, because motives usually can't just be willed away. Deciding not to have a motive usually only drives it beneath your awareness so that it becomes a hidden motive.

One strategy is to make note of your internal motives while you're listening. As you notice your motives in progressively closer and finer detail, you'll eventually become more fully conscious of ulterior motives, and they may even unravel, allowing you to let go and listen just for the sake of listening.

#5 - Reacting to red flag words

Words can provoke a reaction in the listener that wasn't necessarily what the speaker intended. When that happens the listener won't be able to hear or pay full attention to what the speaker is saying.

Red flag words or expressions trigger an unexpectedly strong association in the listener's mind, often because of the listener's private beliefs or experiences.

Good listeners have learned how to minimize the distraction caused by red flag words, but a red flag word will make almost any listener momentarily unable to hear with full attention.

An important point is that the speaker may not have actually meant the word in the way that the listener understood. However, the listener will be so distracted by the red flag that she will not notice what the speaker actually did mean to say.

Red flag words don't always provoke emotional reactions. Sometimes they just cause slight disagreements or misunderstandings. Whenever a listener finds himself disagreeing or reacting, he should be on the lookout for red flag words or expressions.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

When a speaker uses a word or expression that triggers a reflexive association, you as a good listener can ask the speaker to confirm whether she meant to say what you think she said.

When you hear a word or expression that raises a red flag, try to stop the conversation, if possible, so that you don't miss anything that the speaker says. Then ask the speaker to clarify and explain the point in a different way.

#6 - Believing in language

One of the trickiest barriers is "believing in language" -- a misplaced trust in the precision of words.

Language is a guessing game. Speaker and listener use language to predict what each other is thinking. Meaning must always be actively negotiated.

It's a fallacy to think that a word's dictionary definition can be transmitted directly through using the word. An example of that fallacy is revealed in the statement, "I said it perfectly clear, so why didn't you understand?". Of course, the naive assumption here is that words that are clear to one person are clear to another as if the words themselves contained absolute meaning.

Words have a unique effect in the mind of each person, because each person's experience is unique. Those differences can be small, but the overall effect of the differences can become large enough to cause misunderstanding.

A worse problem is that words work by pointing at experiences shared by speaker and listener.

If the listener hasn't had the experience that the speaker is using the word to point at, then the word points at nothing. Worse still, the listener may quietly substitute a different experience to match the word.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

You as a good listener ought to practice mistrusting the meaning of words. Ask the speaker supporting questions to cross-verify what the words mean to him.

Don't assume that words or expressions mean exactly the same to you as they do to the speaker. You can stop the speaker and question the meaning of a word. Doing that too often also becomes an impediment, of course, but if you suspect that the speaker's usage of the word might be slightly different, you ought to take time to explore that, before the difference leads to misunderstanding.

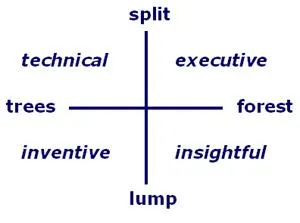

#7 - Mixing up the forest and the trees

A common saying refers to an inability "to see the forest for the trees". Sometimes people pay such close attention to detail, that they miss the overall meaning or context of a situation.

Some speakers are what we will call "trees" people. They prefer concrete, detailed explanations. They might explain a complex situation just by naming or describing its characteristics in no particular order.

Other speakers are "forest" people. When they have to explain complex situations, they prefer to begin by giving a sweeping, abstract, bird's-eye view.

Good explanations usually involve both types, with the big-picture "forest" view providing context and overall meaning, and the specific "trees" view providing illuminating examples.

When trying to communicate complex information, the speaker needs to accurately shift between forest and trees in order to show how the details fit into the big picture. However, speakers often forget to use "turn indicators" to signal that they are shifting from one to another, which can cause confusion or misunderstanding for the listener.

Each style is prone to weaknesses in communication. For example, "trees" people often have trouble telling their listener which of the details are more important and how those details fit into the overall context. They can also fail to tell their listener that they are making a transition from one thought to another -- a problem that quickly shows up in their writing, as well.

"Forest" people, on the other hand, often baffle their listeners with obscure abstractions. They tend to prefer using concepts, but sometimes those concepts are so removed from the world of the senses that their listeners get lost.

"Trees" people commonly accuse "forest" people of going off on tangents or speaking in unwarranted generalities. "Forest" people commonly feel that "trees" people are too narrow and literal.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

You as a good listener can explicitly ask the speaker for overall context or for specific exemplary details, as needed. You should cross-verify by asking the speaker how the trees fit together to form the forest. Having an accurate picture of how the details fit together is crucial to understanding the speaker's thoughts.

An important point to remember is that a "trees" speaker may become confused or irritated if you as the listener try to supply missing context, and a "forest" speaker may become impatient or annoyed if you try to supply missing examples.

A more effective approach is to encourage the speaker to supply missing context or examples by asking him open-ended questions.

Asking open-ended questions when listening is generally more effective than asking closed-ended ones.

For example, an open-ended question such as "Can you give me a concrete example of that?" is less likely to cause confusion or disagreement than a more closed-ended one such as "Would such-and-such be an example of what you're talking about?"

Some speakers may even fail to notice that a closed-ended question is actually a question. They may then disagree with what they thought was a statement of opinion, and that will cause distracting friction or confusion.

The strategy of asking open-ended questions, instead of closed-ended or leading questions, is an important overall component of good listening.

#8 - Over-splitting or over-lumping

Speakers have different styles of organizing thoughts when explaining complex situations. Some speakers, "splitters", tend to pay more attention to how things are different. Other speakers, "lumpers", tend to look for how things are alike. Perhaps this is a matter of temperament.

If the speaker and listener are on opposite sides of the splitter-lumper spectrum, the different mental styles can cause confusion or lack of understanding.

A listener who is an over-splitter can inadvertently signal that he disagrees with the speaker over everything, even if he actually agrees with most of what the speaker says and only disagrees with a nuance or point of emphasis.

That can cause "noise" and interfere with the flow of conversation. Likewise, a listener who is an over-lumper can let crucial differences of opinion go unchallenged, which can lead to a serious misunderstanding later. The speaker will mistakenly assume that the listener has understood and agreed.

It's important to achieve a good balance between splitting (critical thinking) and lumping (metaphorical thinking). Even more important is for the listener to recognize when the speaker is splitting and when she is lumping.

Strategy for overcoming this barrier

An approach to overcoming this barrier when listening is to ask questions to determine more precisely where you agree or disagree with what the speaker is saying, and then to explicitly point that out, when appropriate.

For example, you might say, "I think we have differing views on several points here, but do we at least agree that ... ?" or "We agree with each other on most of this, but I think we have different views in the area of ...."

By actively voicing the points of convergence and divergence, the listener can create a more accurate mental model of the speaker's mind. That reduces the conversational noise that can arise when speaker and listener fail to realize how their minds are aligned or unaligned.

Quadrant of cognitive/explanatory styles

More than one barrier may often be present at once. For example, a speaker might be an over-splitter who has trouble seeing the forest, while the listener is an over-lumper who can see only the forest and never the trees. They will have even more difficulty communicating if one or both also has the habit of "knowing the answer" or "treating discussion as competition".

GOOD LISTENING is arguably one of the most important skills to have in today's complex world. Families need good listening to face complicated stresses together. Corporate employees need it to solve complex problems quickly and stay competitive. Students need it to understand complex issues in their fields. Much can be gained by improving listening skills.

When the question of how to improve communication comes up, most attention is paid to making people better speakers or writers (the "supply-side" of the communication chain) rather than on making them better listeners or readers (the "demand-side").

More depends on listening than on speaking.

An especially skillful listener will know how to overcome many of the deficiencies of a vague or disorganized speaker. On the other hand, it won't matter how eloquent or cogent a speaker is if the listener isn't paying attention.

The listener arguably bears more responsibility than the speaker for the quality of communication.

Technology is often seen as the driver of improved communications. In terms of message transfer, technology certainly does play an essential role. However, communications is much more than just transferring messages. To truly communicate means to learn something about the interior of another person's mind.

Much has been said about the emergence of a "global mind" through technology. Of course, we've noticed that technology, in itself, creates noise and discord as much as it melds minds.

A deeper commitment to better listening is essential in order for technology to fulfill its promise of bringing the world together in real terms.

We can make a difference in the world by learning to listen better and by telling others about better listening. But only if they listen.

Let the Formula EQ Academy be your

success partner.

Achieve success in every area of your life.

NOT A MEMBER YET?

JOIN NOW

Digital Formula

EQ Genius

Academy

$39/mo.

- New Web Portal

- Fully Online

- Do at your own pace

- Supportive training

- Guided Meditations

- Online Community

- Private Academy Chat

- Ask Questions in the Academy Chat

1 Year Live Online Formula

EQ Genius

Academy

$365/yr.

- Live Weekly Online Lesson

- Get Live Online Coaching with Q&A so you can apply these teachings to your life.

- 52 unique Workshops

- Supportive community meetings

- Digital Formula EQ Genius Training Included

One-on-One

Formula EQ Life/Business

Coaching

Month-to-Month

$1200/mo.

- Work directly with Preston and Eldin!

- Massively grow your business and personal life

- Deeply apply the teachings

- Become a true EQ Genius

- This is for people who are very serious about results

- Live Genius Academy Included

- Digital Training Included

Contact

Give us a call

Send us an email

Visit us someday

Scottsdale AZ, USA

or

London, England